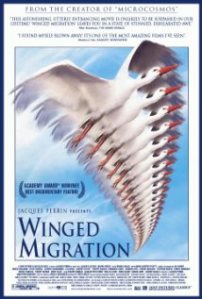

There was a time when my vacation trips would be spent traveling to historical points of interest, exploring museums and art galleries, and learning everything I could about the place I was visiting. In recent years, my downtime is spent differently. I no longer feel motivated to learn facts about specific tourist sites. I just want to travel to new locales and observe. I want to see natural landscapes and soak up the ambiance of the place. I do not want information. I want to feel connected to the universe. I want to see and hear the quiet energy that lies beneath the surface of everyday life. It is a different kind of experience and that is why I enjoyed Winged Migration, an unusual documentary about the yearly migration of birds.

There was a time when my vacation trips would be spent traveling to historical points of interest, exploring museums and art galleries, and learning everything I could about the place I was visiting. In recent years, my downtime is spent differently. I no longer feel motivated to learn facts about specific tourist sites. I just want to travel to new locales and observe. I want to see natural landscapes and soak up the ambiance of the place. I do not want information. I want to feel connected to the universe. I want to see and hear the quiet energy that lies beneath the surface of everyday life. It is a different kind of experience and that is why I enjoyed Winged Migration, an unusual documentary about the yearly migration of birds.

This film tracks a number of species of migratory birds over a span of four years. Some travel over a thousand miles to find food each year; and then when food runs out at their destination, they return the same distance to their point of origin to find nourishment. They miraculously always fly the same route using the stars and familiar landmarks on land, in the sea, and in the sky to locate food sources and to get back home. Familiarity helps them to survive just as it helps us navigate difficult moments in life. In moments of crisis, we can return to our old routines and derive some stability in a stressful environment or situation.

Using in-flight cameras, the bulk of footage in the film consists of birds flying in the air. You can hear the air move under their wings and you have the sensation that you are flying alongside the birds. You are with them in the cold snow of the Arctic regions, you are with them when they escape a powerful avalanche, and you are with them in the bloom of summer with trees and flowers all around. The terrain, seen from the perspective of the birds, is breathtaking. The film truly is a visual work of art.

There is almost no narration in the film. There are just scenes of different species of birds traveling thousands of miles, crossing continents and oceans in search of food. There is no conventional plot. Instead, there are extraordinary images of birds desperately flapping their wings flying from one country to another. The key theme unifying all these migrations is survival. The birds cannot survive if they stay where they are. Movement is critical for survival.

The dominant visual in Winged Migration is a bird desperately flapping its wings to stay airborne on its long journey. For me, it was a metaphor of the human journey through life. All of us want to survive and thrive in life in spite of the adversities and challenges we all face. Like the bird, we have to keep moving and not allow challenges and occasional failures to cripple us.

The Biblical metaphor which captures this Jewish approach to confronting life’s challenges is the ramp upon which the priest walks when he approaches the altar to offer sacrifices. The priest does not climb steps. Rather he traverses a ramp, which has no natural place to stop or rest. The message to the priest, and for all men since the priest represents all of us, is to constantly strive, not to give up in the face of adversity. The Sages of the Talmud suggest that a successful life requires constant forward progress, constant movement and activity. The birds in Winged Migration teach us this valuable lesson.