House of Sand and Fog may be the saddest film I have ever seen. It demonstrates the tragic consequences of failed communication, when two people are, metaphorically speaking, on opposite sides of the table unable to find a compromise middle ground before it is too late to avoid catastrophe.

House of Sand and Fog may be the saddest film I have ever seen. It demonstrates the tragic consequences of failed communication, when two people are, metaphorically speaking, on opposite sides of the table unable to find a compromise middle ground before it is too late to avoid catastrophe.

There is a well-known story in the Talmud (Gittin 55b) explaining the origins of the destruction of the Holy Second Temple in Jerusalem. A man wanted to invite all his friends to a big party. He sent an invitation to his friend Kamtza, but his servant mistakenly delivered the invite to his enemy Bar Kamtza.

When Bar Kamtza showed up at the feast, he was told to leave. Rather than be embarrassed, Bar Kamtza offered to pay for the entire feast. In spite of this generous offer, Bar Kamtza was ejected from the festivities. The rabbis who were present and witnessed this exchange said nothing, and Bar Kamtza assumed they were complicit in causing his embarrassment. In anger, he went to the Roman authorities and said the Jews were disloyal to Rome. The Romans took this slander as truth and proceeded to attack and destroy both the Jews and their Temple. Self-absorption, misunderstanding, an inability to see things from another’s perspective led to this tragedy. This is the essential narrative crux of House of Sand and Fog.

Kathy Nicolo is depressed. Her husband has left her months ago. She lives alone in small house near San Francisco Bay. Because of her failure to respond to eviction notices for non-payment of county fees, her home is sold at auction to Massoud Amir Behrani, a former Iranian Army Colonel who fled Iran when the Ayatollah assumed control of the country. For Behrani, the purchase of the home represents his final opportunity to gain respect for himself, for his wife, Naderah, and for his son, Esmail. His goal is to fix up the dilapidated house and sell it for four times the purchase price in order to provide a comfortable life for this wife and for a college education for his son.

Kathy feels the county has illegally has sold her home and enlists the aid of a lawyer and Deputy Sherriff Lester Burden to help her reclaim her house. And so begins an acerbic relationship between Kathy and Behrani, both of whom assume they are in the right.

Kathy willfully destroys the lives of others in her quest to get her house back, while Behrani does not understand the desperate straits that motivate her actions. Things reach a breaking point when Lester, posing as another policeman, threatens Behrani with deportation of his family back to Iran where certain death awaits them. Behrani, who is a bonafide American citizen, discovers that he is the victim of extortion and reports Lester’s misrepresentation to the internal affairs department of the police department, further driving a wedge between Kathy and Behrani.

Tensions escalate until an unspeakable tragedy suddenly awakens sympathy for the other. Calamity has the power to take a person out of his own malaise and makes him aware of the troubles of other human beings. It is a painful way to learn.

Jewish law and lore places a high priority on harmonious relations between people. Knowing that everyone is created in the image of God means that everyone is important, everyone is unique and has infinite potential. Therefore, one cannot be dismissive of anyone, for everyone deserves respect, even if they do not agree with you.

Our Sages tell us not to hold grudges or be vengeful. Rather, anytime we encounter friction, we need to try and work it out. We need to ask ourselves if we are at fault for miscommunication. Once we recognize our own faults and correct them, we can bring the ultimate redemption of mankind one step closer. Kathy Nicola learns this lesson too late.

I once employed a teacher who wanted very much to succeed in the classroom. The model lesson that he gave before being hired was superb and I thought he would be a great asset to the school.

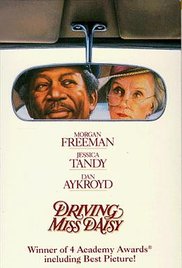

I once employed a teacher who wanted very much to succeed in the classroom. The model lesson that he gave before being hired was superb and I thought he would be a great asset to the school. As a youngster, I lived in a neighborhood of low income housing in Mt. Vernon, New York, predominantly occupied by black families. In my elementary and junior high schools, there was a sizeable population of black students, and I was friendly with some of them. There was Dickie Fisher, Joyce Jones, Wendell Tyree, Linwood Lee, and Quentin Pair. Their names fascinated me and gave expression to the unique personalities of each one of them.

As a youngster, I lived in a neighborhood of low income housing in Mt. Vernon, New York, predominantly occupied by black families. In my elementary and junior high schools, there was a sizeable population of black students, and I was friendly with some of them. There was Dickie Fisher, Joyce Jones, Wendell Tyree, Linwood Lee, and Quentin Pair. Their names fascinated me and gave expression to the unique personalities of each one of them. In retrospect, I have had a wonderful career in Jewish education, the highlight of which was in Atlanta from 1970 through 1998. The school I led was Yeshiva High School of Atlanta and its enrollment grew from 36 to approximately 200 during my long and occasionally turbulent tenure.

In retrospect, I have had a wonderful career in Jewish education, the highlight of which was in Atlanta from 1970 through 1998. The school I led was Yeshiva High School of Atlanta and its enrollment grew from 36 to approximately 200 during my long and occasionally turbulent tenure. As a child, I often read Classic Comics, which presented classic novels in cartoons. I remember reading one of the Sherlock Holmes novels in this format and being fascinated by Holmes’s ability to focus on the details of a case and ignoring extraneous details.

As a child, I often read Classic Comics, which presented classic novels in cartoons. I remember reading one of the Sherlock Holmes novels in this format and being fascinated by Holmes’s ability to focus on the details of a case and ignoring extraneous details. I live life as it unfolds in the present moment. I do not recall saying to myself “What if I had done this rather than that.” Yet I have friends who continually ask themselves “what would my life be like if I had made this decision rather than that decision.” The reality is that we cannot turn back the clock and decisions we made years ago cannot be changed. Those decisions affect our lives many years later.

I live life as it unfolds in the present moment. I do not recall saying to myself “What if I had done this rather than that.” Yet I have friends who continually ask themselves “what would my life be like if I had made this decision rather than that decision.” The reality is that we cannot turn back the clock and decisions we made years ago cannot be changed. Those decisions affect our lives many years later. I remember a weird story from my youth. I attended public school and in the afternoon went to a synagogue Hebrew school where I learned how to read Hebrew and lead the services. Although I was a good student, I occasionally was mischievous. One cold, snowy day, I decided to play a prank on the teacher and placed a snowball on his chair expecting him to get up right way when he discovered the moisture on his seat.

I remember a weird story from my youth. I attended public school and in the afternoon went to a synagogue Hebrew school where I learned how to read Hebrew and lead the services. Although I was a good student, I occasionally was mischievous. One cold, snowy day, I decided to play a prank on the teacher and placed a snowball on his chair expecting him to get up right way when he discovered the moisture on his seat. As a child with a Downs Syndrome sister, I recall in the 1950s families with Downs Syndrome children often kept their kids in the proverbial closet. My mother and father thought differently. They felt Carol, their daughter, needed to be visible in the community and that the community should provide the resources for such kids to develop their potential to the fullest extent possible. That’s why my mother fought for the establishment for a school in Westchester County for the mentally retarded and, when Carol was older, for the establishment of a retarded children’s workshop in White Plains so that Carol could feel and be productive in her mature years.

As a child with a Downs Syndrome sister, I recall in the 1950s families with Downs Syndrome children often kept their kids in the proverbial closet. My mother and father thought differently. They felt Carol, their daughter, needed to be visible in the community and that the community should provide the resources for such kids to develop their potential to the fullest extent possible. That’s why my mother fought for the establishment for a school in Westchester County for the mentally retarded and, when Carol was older, for the establishment of a retarded children’s workshop in White Plains so that Carol could feel and be productive in her mature years. A family member recently bought a foreclosure home in Florida. A foreclosure is a home owned by the bank because of the failure of the owner to pay his mortgage. From a distance, it looks great for the new purchaser who can acquire a home at a very favorable price; but, up close, a foreclosure has a dark side and can signify a very human tragedy. This is depicted in 99 Homes, an unsettling look at the consequences of foreclosure on decent people who, for a variety of reasons, can’t make ends meet.

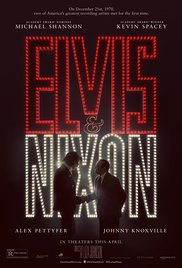

A family member recently bought a foreclosure home in Florida. A foreclosure is a home owned by the bank because of the failure of the owner to pay his mortgage. From a distance, it looks great for the new purchaser who can acquire a home at a very favorable price; but, up close, a foreclosure has a dark side and can signify a very human tragedy. This is depicted in 99 Homes, an unsettling look at the consequences of foreclosure on decent people who, for a variety of reasons, can’t make ends meet. As a young teenager in Mt. Vernon, New York, I was an avid fan of Elvis Presley. I awaited the release of each new single and purchased the albums as they became available. I even combed my hair like Elvis and grew sideburns like him. I thought to look like him was cool; as a result, many of my fellow high school students viewed me as an enigma, not knowing if I was a sweet Jewish kid or a rock and roller ready to rumble.

As a young teenager in Mt. Vernon, New York, I was an avid fan of Elvis Presley. I awaited the release of each new single and purchased the albums as they became available. I even combed my hair like Elvis and grew sideburns like him. I thought to look like him was cool; as a result, many of my fellow high school students viewed me as an enigma, not knowing if I was a sweet Jewish kid or a rock and roller ready to rumble.