I once employed a teacher who wanted very much to succeed in the classroom. The model lesson that he gave before being hired was superb and I thought he would be a great asset to the school.

I once employed a teacher who wanted very much to succeed in the classroom. The model lesson that he gave before being hired was superb and I thought he would be a great asset to the school.

Things went well in the first year of his employment, but then problems emerged. He did not take criticism well and blamed others for his own shortcomings. Either the students were not cooperative or the parents were conspiring against him, deliberately sabotaging his teaching efforts. Eventually I had to release him because of his constant complaining, which bordered on paranoia. I felt that there was a danger that he might infect the kids with his overwhelming negativity and inability to respond to criticism constructively.

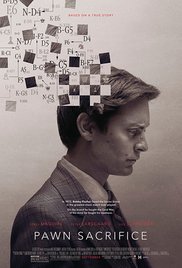

This notion that talented people are sometimes sabotaged in life because of their own self-induced psychological issues underpins the sad narrative of Bobby Fischer, the chess genius. Fischer vanquished Russian Boris Spassky in the chess match of the century, yet suffered serious mental issues that, at the end of his life, left him a vagrant and alone, espousing conspiracy theories to anyone who would listen.

The film, which begins with Bobby as a child, depicts him being exposed to conspiracy theories by his mother, a Russian immigrant, who fears a possible social revolution in the United States, in which ordinary citizens are spied upon. A loner as a young boy, Bobby learns to play chess on his own, and it soon becomes his obsession. His mentor, a local chessmaster, creates opportunities that lead Bobby to the arena of professional chess championships.

After he becomes the youngest grand master ever, Bobby senses that the Russians are out to get him and responds with vitriolic outbursts that surprise even his fans. He seems unhinged mentally when he decides to leave the professional world of chess because of suspicions that the Russians are trying to isolate him and make it impossible for him to win.

Sensing that it is important for an American to win the World Chess Championship in the era of the Cold War, an American lawyer volunteers his services to Fischer to enable him to modify the tournament rules so that he will have a fair chance to win future competitions. Bobby then turns to William Lombardy, a former World Junior Chess Champion, to be his second, a man who will encourage Bobby to mitigate his excessive demands and return to winning tournaments. Bobby then re-enters the world of professional chess.

Although Bobby projects confidence and invincibility, we sense insecurity and mental psychosis because of the pressure to win every match. His first match with Russian Boris Spassky, the reigning World Chess Champion, ends in defeat; but Bobby and Spassky eventually meet again in Reykjavik, Iceland, for a historic match to determine who, indeed, is the world’s greatest chess player. It is a sporting event like no other and it captures the excitement of chess fans all over the world.

Maimonides, the great medieval Jewish thinker, promotes the golden path in life, avoiding extremes in lifestyle and character traits. Moreover, the Sages of the Talmud always espouse living a live of balance. They especially discouraged a life motivated by jealousy and a life in which the desire for honor and recognition dominates.

Bobby Fischer does not lead a balanced life. He is a troubled child who grows up to be a troubled adult. Focused on chess alone, he turns inward and divorces himself from the real world. His inability to see things from the perspective of the other does not allow him to appreciate the contributions of those around him. All he sees are people who want to take advantage of his celebrity. Such a narrow, extreme view of life leads to paranoia and emotional instability.

Bobby Fischer’s narrative in Pawn Sacrifice is a cautionary tale of what can happen when you lead a life without balance, when you are concerned only with your own welfare and no one else’s.

As a youngster, I lived in a neighborhood of low income housing in Mt. Vernon, New York, predominantly occupied by black families. In my elementary and junior high schools, there was a sizeable population of black students, and I was friendly with some of them. There was Dickie Fisher, Joyce Jones, Wendell Tyree, Linwood Lee, and Quentin Pair. Their names fascinated me and gave expression to the unique personalities of each one of them.

As a youngster, I lived in a neighborhood of low income housing in Mt. Vernon, New York, predominantly occupied by black families. In my elementary and junior high schools, there was a sizeable population of black students, and I was friendly with some of them. There was Dickie Fisher, Joyce Jones, Wendell Tyree, Linwood Lee, and Quentin Pair. Their names fascinated me and gave expression to the unique personalities of each one of them. In retrospect, I have had a wonderful career in Jewish education, the highlight of which was in Atlanta from 1970 through 1998. The school I led was Yeshiva High School of Atlanta and its enrollment grew from 36 to approximately 200 during my long and occasionally turbulent tenure.

In retrospect, I have had a wonderful career in Jewish education, the highlight of which was in Atlanta from 1970 through 1998. The school I led was Yeshiva High School of Atlanta and its enrollment grew from 36 to approximately 200 during my long and occasionally turbulent tenure. As a child, I often read Classic Comics, which presented classic novels in cartoons. I remember reading one of the Sherlock Holmes novels in this format and being fascinated by Holmes’s ability to focus on the details of a case and ignoring extraneous details.

As a child, I often read Classic Comics, which presented classic novels in cartoons. I remember reading one of the Sherlock Holmes novels in this format and being fascinated by Holmes’s ability to focus on the details of a case and ignoring extraneous details. I live life as it unfolds in the present moment. I do not recall saying to myself “What if I had done this rather than that.” Yet I have friends who continually ask themselves “what would my life be like if I had made this decision rather than that decision.” The reality is that we cannot turn back the clock and decisions we made years ago cannot be changed. Those decisions affect our lives many years later.

I live life as it unfolds in the present moment. I do not recall saying to myself “What if I had done this rather than that.” Yet I have friends who continually ask themselves “what would my life be like if I had made this decision rather than that decision.” The reality is that we cannot turn back the clock and decisions we made years ago cannot be changed. Those decisions affect our lives many years later. I remember a weird story from my youth. I attended public school and in the afternoon went to a synagogue Hebrew school where I learned how to read Hebrew and lead the services. Although I was a good student, I occasionally was mischievous. One cold, snowy day, I decided to play a prank on the teacher and placed a snowball on his chair expecting him to get up right way when he discovered the moisture on his seat.

I remember a weird story from my youth. I attended public school and in the afternoon went to a synagogue Hebrew school where I learned how to read Hebrew and lead the services. Although I was a good student, I occasionally was mischievous. One cold, snowy day, I decided to play a prank on the teacher and placed a snowball on his chair expecting him to get up right way when he discovered the moisture on his seat. As a child with a Downs Syndrome sister, I recall in the 1950s families with Downs Syndrome children often kept their kids in the proverbial closet. My mother and father thought differently. They felt Carol, their daughter, needed to be visible in the community and that the community should provide the resources for such kids to develop their potential to the fullest extent possible. That’s why my mother fought for the establishment for a school in Westchester County for the mentally retarded and, when Carol was older, for the establishment of a retarded children’s workshop in White Plains so that Carol could feel and be productive in her mature years.

As a child with a Downs Syndrome sister, I recall in the 1950s families with Downs Syndrome children often kept their kids in the proverbial closet. My mother and father thought differently. They felt Carol, their daughter, needed to be visible in the community and that the community should provide the resources for such kids to develop their potential to the fullest extent possible. That’s why my mother fought for the establishment for a school in Westchester County for the mentally retarded and, when Carol was older, for the establishment of a retarded children’s workshop in White Plains so that Carol could feel and be productive in her mature years. A family member recently bought a foreclosure home in Florida. A foreclosure is a home owned by the bank because of the failure of the owner to pay his mortgage. From a distance, it looks great for the new purchaser who can acquire a home at a very favorable price; but, up close, a foreclosure has a dark side and can signify a very human tragedy. This is depicted in 99 Homes, an unsettling look at the consequences of foreclosure on decent people who, for a variety of reasons, can’t make ends meet.

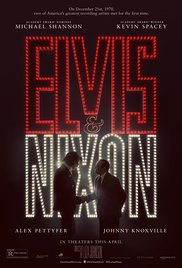

A family member recently bought a foreclosure home in Florida. A foreclosure is a home owned by the bank because of the failure of the owner to pay his mortgage. From a distance, it looks great for the new purchaser who can acquire a home at a very favorable price; but, up close, a foreclosure has a dark side and can signify a very human tragedy. This is depicted in 99 Homes, an unsettling look at the consequences of foreclosure on decent people who, for a variety of reasons, can’t make ends meet. As a young teenager in Mt. Vernon, New York, I was an avid fan of Elvis Presley. I awaited the release of each new single and purchased the albums as they became available. I even combed my hair like Elvis and grew sideburns like him. I thought to look like him was cool; as a result, many of my fellow high school students viewed me as an enigma, not knowing if I was a sweet Jewish kid or a rock and roller ready to rumble.

As a young teenager in Mt. Vernon, New York, I was an avid fan of Elvis Presley. I awaited the release of each new single and purchased the albums as they became available. I even combed my hair like Elvis and grew sideburns like him. I thought to look like him was cool; as a result, many of my fellow high school students viewed me as an enigma, not knowing if I was a sweet Jewish kid or a rock and roller ready to rumble. When I taught Hamlet some years ago to a high school class in Atlanta, a student voiced surprise that Ophelia, a woman deeply in love with Hamlet, committed suicide. It prompted a class discussion about how friends experience great pain when they see a loved one suffering.

When I taught Hamlet some years ago to a high school class in Atlanta, a student voiced surprise that Ophelia, a woman deeply in love with Hamlet, committed suicide. It prompted a class discussion about how friends experience great pain when they see a loved one suffering.