Occasionally I meet old friends whose life has passed them by. As young men, they seemed so full of promise. I thought they would be professional successes in adulthood with loving wives and children. Yet something happened along the way. They were barely making a living, had not married, and were a shell of their former selves.

Occasionally I meet old friends whose life has passed them by. As young men, they seemed so full of promise. I thought they would be professional successes in adulthood with loving wives and children. Yet something happened along the way. They were barely making a living, had not married, and were a shell of their former selves.

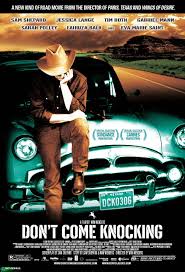

They tried to keep up a happy façade, but I sensed an undercurrent of profound sadness beneath the superficial smile. That narrative arc permeates Don’t Come Knocking, the elegiac narrative of Howard Spence, an aging movie star who recklessly tossed away every opportunity to lead a fulfilling family and professional life.

The movie begins with Howard suddenly leaving a film shoot of his latest western, which is being filled in the Utah desert. He rides away on a horse, changes his clothes so that he will be unrecognizable, and decides to reconnect with his mother whom he has not seen for thirty years. He travels to his hometown of Elko, Nevada to see her.

In the interim, the movie company launches a search for him led by Mr. Sutter, an insurance executive determined to find Howard and return him to the set. For the moment, the production is stalled and cannot continue. Tension mounts on the set because for each day the film is delayed, there is great financial loss to the studio. Indeed, without Howard returning and completing his scenes, the director cannot wrap up the film. Sutter’s search for Howard is the subplot of Howard’s personal journey to find himself after years of behavioral excess.

Howard’s reunion with his mother, after thirty years of absence, is both touching and weird. They speak with a familiarity that suggests a loving and authentic rapport with each other, but Howard’s conversation with her seems like the tentative remarks of a teenager who has stayed out late one night. Howard is almost clueless about the mess he has made with his life until he peruses his mother’s scrapbooks, which contain newspaper accounts of Howard’s self-destructive behavior with drugs and women, his barroom brawls, and his movie debacles.

His mother informs him that he has a son in Butte, Montana. This piques Howard’s curiosity and he decides to find him. While in Butte, he meets Doreen, his old flame and the mother of Earl, his son. Both Doreen and Earl are puzzled by Howard’s return; they resent him intruding into their lives after an absence of twenty years.

Confronting his past is not easy for Howard either. His emotional malaise is captured in an iconic scene in which he sits on a couch that has been left abandoned in the middle of an empty street. Howard sits quietly while the camera pans around him from dusk to dawn. He is still, but everything around him is moving. The scene suggests that for many years he has not adapted to the changes going on around him. He cries, he reflects, he meditates, and finally begins to understand the price he has paid for his youthful folly.

How Howard tries to reconcile with Doreen and Earl makes for a compelling and, at the same time, an oblique family drama. Don’t Come Knocking does not have a neat ending, but it does intimate that even in the most extreme of circumstances, people can find a way to communicate and adjust to new emotional realities.

Howard Spence, after years of profligate living, begins to comprehend the damage he has inflicted on others by his casual attitude towards marriage and fatherhood. He cannot alter the past; but he can be wiser, at least in some small way, for the rest of his life.

There is a story told about a great nineteenth century ethicist, Rabbi Israel Salanter, who happened to be walking late one night in front of the home of a shoemaker. Rabbi Salanter observed the man was working by the light of flickering candle. He asked the shoemaker why he was laboring so late at night. He replied: “As long as the candle is still burning, it is still possible to accomplish and to mend.”

This is an insight that Howard gains through the crucible of painful human experience. He cannot change the past; but as long as he is alive, he can make connections in the present that make him relevant to lost loves and forsaken children.

I was a mediocre high school student at A.B. Davis High School in Mt. Vernon, New York. One day when I had to turn in a book report about a book I had not read, I decided to copy a friend’s paper. I did not realize that my friend had plagiarized his paper, so my act of plagiarism was once removed from the original act. Nonetheless, I was submitting work that was not mine. My history teacher, Mr. Elman, for whom the report was written, discovered my duplicity and failed me for the course. He was very disappointed in me and I felt ashamed of what I did.

I was a mediocre high school student at A.B. Davis High School in Mt. Vernon, New York. One day when I had to turn in a book report about a book I had not read, I decided to copy a friend’s paper. I did not realize that my friend had plagiarized his paper, so my act of plagiarism was once removed from the original act. Nonetheless, I was submitting work that was not mine. My history teacher, Mr. Elman, for whom the report was written, discovered my duplicity and failed me for the course. He was very disappointed in me and I felt ashamed of what I did. On rare occasions, I have been confronted with having to make a decision knowing that if I decide one way, I will hurt someone I care about; and if I decide differently, I will hurt someone else. Either way, I will wind up alienating a friend.

On rare occasions, I have been confronted with having to make a decision knowing that if I decide one way, I will hurt someone I care about; and if I decide differently, I will hurt someone else. Either way, I will wind up alienating a friend. In the 1960s, when I was an undergraduate student at Yeshiva University, one of my good friends told me about a student group that traveled once a week to the home of Rabbi Avigdor Miller, a celebrated Torah scholar and ethicist. Once there, the revered rabbi would speak for about ten to fifteen minutes about a particular character trait and then give the students an assignment that would help us integrate that character trait into our daily lives.

In the 1960s, when I was an undergraduate student at Yeshiva University, one of my good friends told me about a student group that traveled once a week to the home of Rabbi Avigdor Miller, a celebrated Torah scholar and ethicist. Once there, the revered rabbi would speak for about ten to fifteen minutes about a particular character trait and then give the students an assignment that would help us integrate that character trait into our daily lives. Terrorism is very much a part of the world’s landscape at this point in history. Terrorist attacks occur not only in Israel, but in the United States, France, and Belgium among other countries. The world is a scary place, and many are trying to figure out what is the intellectual and emotional appeal of this aberrant behavior, which destabilizes the world. The Dancer Upstairs is a quiet, thoughtful, and tense film that gives us some understanding of the philosophical and practical motives that drive terrorists in the modern world.

Terrorism is very much a part of the world’s landscape at this point in history. Terrorist attacks occur not only in Israel, but in the United States, France, and Belgium among other countries. The world is a scary place, and many are trying to figure out what is the intellectual and emotional appeal of this aberrant behavior, which destabilizes the world. The Dancer Upstairs is a quiet, thoughtful, and tense film that gives us some understanding of the philosophical and practical motives that drive terrorists in the modern world. From my early childhood, I was an avid moviegoer. My mother took me regularly; and when I grew older, I continued to go frequently. Movies captivated me because they transported me to faraway places and to exciting adventures. I lived in a small town and movies were my ticket to Neverland. Although I enjoyed movies, I generally did not think of them as accurate descriptions of the real world. They were fantasies, pleasing entertainments, and that was it.

From my early childhood, I was an avid moviegoer. My mother took me regularly; and when I grew older, I continued to go frequently. Movies captivated me because they transported me to faraway places and to exciting adventures. I lived in a small town and movies were my ticket to Neverland. Although I enjoyed movies, I generally did not think of them as accurate descriptions of the real world. They were fantasies, pleasing entertainments, and that was it. I began my doctoral studies in English in Atlanta in 1972. It was intended to be a 5-year program, but it took much longer because I was busy with earning a living and rearing a young family. I finally received my PhD in 1984, twelve years after I started.

I began my doctoral studies in English in Atlanta in 1972. It was intended to be a 5-year program, but it took much longer because I was busy with earning a living and rearing a young family. I finally received my PhD in 1984, twelve years after I started. The Ethics of the Fathers tells us that one hour repenting and doing good deeds in this world is better than life in the world-to-come. Why? The Sages explain: we can only exercise our free will while we are alive. Therefore, we can choose to do good deeds only when we are alive. Doing good deeds is our mission on earth, so everything we do or don’t do influences our eternal destiny. That is why life in this world is so precious.

The Ethics of the Fathers tells us that one hour repenting and doing good deeds in this world is better than life in the world-to-come. Why? The Sages explain: we can only exercise our free will while we are alive. Therefore, we can choose to do good deeds only when we are alive. Doing good deeds is our mission on earth, so everything we do or don’t do influences our eternal destiny. That is why life in this world is so precious. In the late 1960s, I was a graduate student in English at Hunter College, a division of the City University of New York. I read literary critics like Irving Howe and Lionel Trilling, and breathed in the air of the New York intellectual scene.

In the late 1960s, I was a graduate student in English at Hunter College, a division of the City University of New York. I read literary critics like Irving Howe and Lionel Trilling, and breathed in the air of the New York intellectual scene. Growing up in the 50s and 60s, dating for marriage was a very straightforward process. You met, dated for several months, and then came the moment of truth. Do you propose marriage or move on to dating someone else?

Growing up in the 50s and 60s, dating for marriage was a very straightforward process. You met, dated for several months, and then came the moment of truth. Do you propose marriage or move on to dating someone else?