Some people are passionate about food; others eat simply to be nourished, lacking interest in food preparation and presentation. I remember watching one of my Torah teachers eating a piece of gefilte fish almost every day for lunch in the Yeshiva. He ate at his desk in the study hall and did not want to waste a moment in walking to a nearby restaurant.

Some people are passionate about food; others eat simply to be nourished, lacking interest in food preparation and presentation. I remember watching one of my Torah teachers eating a piece of gefilte fish almost every day for lunch in the Yeshiva. He ate at his desk in the study hall and did not want to waste a moment in walking to a nearby restaurant.

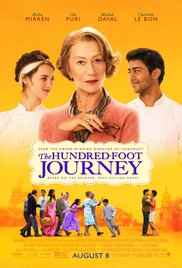

I also vividly recall spending a Friday night meal with the two heads of the Yeshiva I attended in ninth grade. I accompanied them on a fund-raising outing to the Five Towns where they attempted to storm local pulpits and appeal for money to sustain the Yeshiva in difficult financial times. On Friday night, our main course consisted of hard-boiled eggs, but that did not dampen the rabbis’ enthusiasm for the holy Sabbath. They sang sacred melodies until the wee hours of the morning. In contrast, in The Hundred-Foot Journey, money does not limit the ability of people to eat fine food, and all the characters are students and worshippers at the shrine of good cuisine.

Because of political turmoil and danger to life in Mumbai, India, Hassan Kadam and his family move to France where they hope to open a restaurant similar to one they owned in Mumbai. When their van breaks down, they are forced to rely on the kindness of strangers and one kind stranger does appear. She is Marguerite, a young woman who volunteers to take them to a local car mechanic and who also serves them platters of scrumptious and attractive food. The Kadam family is impressed both with her generosity and with her cooking.

While waiting for the repair, Papa Kadam wanders around the town and discovers an abandoned restaurant for sale. He sees the purchase of the restaurant as somehow divinely ordained, a message from his deceased wife that his car did not break down in this village for no reason, but rather to enable him to find a suitable location for his restaurant. Against family objections, he buys the property and the family works diligently to transform the decrepit property into Maison Mumbai, a food emporium specializing in Indian cuisine.

All is not fine, however, when Madame Malory, the owner of a award-winning restaurant across the street, about 100 feet away, sees Maison Mumbai as a serious competitor encroaching on her business. Meanwhile, Hassan, a gifted chef, strikes up a friendship with Marguerite who he discovers is the sous chef at the competing restaurant. She shares with him her passion and love for cooking food.

War breaks out between Papa Kadam and Madame Malory when Madame Malory asks to see the menu of Maison Mumbai, and then proceeds to go the market and purchase all the ingredients that Papa needs to cook his food. Papa retaliates by doing the same thing to Madame Malory, and so the hostilities continue.

Tempers boil until someone torches Maison Mumbai. Then Madame Malory, feeling guilty for encouraging a negative attitude towards her competitor, tries to expiate her sin by helping to fix the damaged restaurant. Papa and Madame become friends and Hassan becomes the bridge of their reconciliation.

Clearly recognizing Hassan’s amazing talents as a chef, they both encourage him to go to Paris where he will fine tune and broaden his cooking repertoire in the world-class restaurants of the city. Hassan, however, is conflicted during his sojourn in Paris. Does he truly want to be in the rarefied ambiance of one of the great culinary cities of the world, or does he want to be with Marguerite in his adopted hometown in rural France? Wherein lies his destiny?

Food preparation and presentation is at the heart of The Hundred-Foot Journey, but the film suggests that there are more important things that motivate people. It is good to appreciate passionately the sundry varieties of food that God has given us, but it is more important to passionately value our human connections, which endure beyond mealtime.

For the Jew, the Sabbath is the day that celebrates the enjoyment of food. The Sabbath table is supposed to be beautiful and enjoyable because it marks the Sabbath as a day different from the rest of the week. During the week, the emphasis is on the nourishment value of food. The Jerusalem Talmud states: “The world can live without wine, but it cannot live without water; the world can live without peppers, but it cannot live without salt.” The comment is a reminder of the value of simple fare that enables us to live. We should eat to live and not live to eat.

There is a brief scene in Beyond the Sea, a biopic of singer Bobby Darin, which resonates with me personally. Bobby unbuttons his shirt and reveals his scar from open-heart surgery. It looks like a long zipper on his chest. I, too, have had open-heart surgery and remember other patients telling me I am now a member of the “zipper club,” all of whose members brandish an extended scar on their chest.

There is a brief scene in Beyond the Sea, a biopic of singer Bobby Darin, which resonates with me personally. Bobby unbuttons his shirt and reveals his scar from open-heart surgery. It looks like a long zipper on his chest. I, too, have had open-heart surgery and remember other patients telling me I am now a member of the “zipper club,” all of whose members brandish an extended scar on their chest. When I was in high school, I had a part-time job at a local pharmacy, working the evening shift from 4 PM until 11:30 and all day Sunday. It was the only store open on Sunday during the late 1950s, before the days of 24/7, or 24/6 in Israel.

When I was in high school, I had a part-time job at a local pharmacy, working the evening shift from 4 PM until 11:30 and all day Sunday. It was the only store open on Sunday during the late 1950s, before the days of 24/7, or 24/6 in Israel.