My wife is an artist. She has perfected a technique called fabric fusion. She starts off with a gray scale photograph and then overlays it with acrylic paints and hand-dyed silks. She has had exhibits of her work at the Tel Aviv Opera House and at the Jerusalem Theatre, both prestigious locations to show art. She sells her work, but she primarily paints because it satisfies her creative urge.

My wife is an artist. She has perfected a technique called fabric fusion. She starts off with a gray scale photograph and then overlays it with acrylic paints and hand-dyed silks. She has had exhibits of her work at the Tel Aviv Opera House and at the Jerusalem Theatre, both prestigious locations to show art. She sells her work, but she primarily paints because it satisfies her creative urge.

What is important is not the money she earns through her art, but the creative experience of producing art that people can enjoy. She regards her artistic work as part of her divine mission.

Occasionally, she asks me to critique a painting, but I feel inadequate to the task. I very much feel that art is in the eye of the beholder. I cannot predict what someone will like.

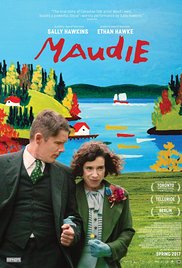

In the final analysis, enduring art can spring from anywhere, even from a remote country village in Nova Scotia. This is what happens in Maudie, the true story of Maudie Dowley, a woman with severe arthritis who develops an iconic ability to paint flowers and birds that appeal to a broad cross-section of people that appreciate her simple but powerful expressions of nature’s beauty.

Rather than live with her highly judgmental Aunt Ida, Maudie decides to strike out on her own and find a job that will enable her to support herself and live independently. Serendipitously, she meets Everett Lewis, a coarse and laconic fish peddler who is seeking a cleaning lady for his home in return for providing room and board and a meager salary. Maudie applies for the job and Everett agrees to try her out.

While employed at his home, Maudie begins to paint parts of the house including shelves, walls, and windows with decorations of flowers and birds. One of Everett’s customers, Sandra, who lives in New York City, is fascinated by Maudie’s art and offers to pay her money for her cards and paintings. Her patronage of Maudie’s art leads to more and more commissions, eventually reaching the eyes of Richard Nixon, who purchases one of her works.

Eventually, Everett and Maudie marry and learn to love one another even though they have totally different temperaments and worldviews. Their marriage is stormy, but in the end it is satisfying to both. Maudie’s ability to see beauty in the ordinary cycle of nature sustains her as she manages her tumultuous relationship with Everett.

In the daily Jewish liturgy, God is described as renewing the creation every day. The message of the prayer is to understand that the beauty of nature manifests itself in ordinary days. It is not a special event. Each day is an opportunity to proclaim the significance of daily miracles, which inform our lives all day long. The challenge is to view nature with fresh eyes. Maudie is able to do this especially when she sees nature through a window. She reflects: “How I love a window. It’s always different. The whole of life. The whole of life already framed. Right there.”

The great medieval sage Maimonides viewed the natural world as a testament to God’s grandeur. In discussing the foundational principles of the Jewish faith, he writes that we can get close to God not only by studying holy words, but also by observing holy works, the everyday miracles that present themselves through natural phenomena. A mountain, a flower, a river, a tree can remind us of the inherent beauty in the world and bring us close to God.

Maudie, a simple soul, is able to transcend her physical limitations when she sees nature in a multi-faceted way. Nature for her is never random or chaotic. Rather it reflects a divine beauty hidden in the flora around us.

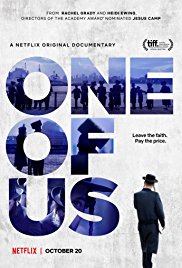

I live in a city in Israel where there are many charedim, ultra-Orthodox Jews. I do not wear the same clothes as they do. They wear mostly black coats and white shirts and live in a different neighborhood. But occasionally I meet them in the local synagogue since both of us are obligated to pray with a quorum of ten men, a minyan, three times a day.

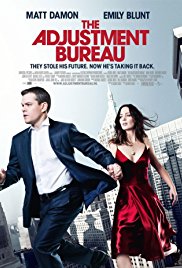

I live in a city in Israel where there are many charedim, ultra-Orthodox Jews. I do not wear the same clothes as they do. They wear mostly black coats and white shirts and live in a different neighborhood. But occasionally I meet them in the local synagogue since both of us are obligated to pray with a quorum of ten men, a minyan, three times a day. As a rabbi, I have often been asked questions relating to destiny versus free will. Can we change our destiny by exercising our free will? It is a complicated question and, from a theological perspective, not easily answered. It seems, however, that Judaism has an approach to looking at the problem. Let me explain. I have been involved in cases where congregants have someone in their family facing death. One traditional response to such a dire situation is to change the name of the person in a life-threatening situation. By doing so, we create an alternative ending, namely, life instead of death. I asked one of my Torah teachers how this works, and this is what he told me.

As a rabbi, I have often been asked questions relating to destiny versus free will. Can we change our destiny by exercising our free will? It is a complicated question and, from a theological perspective, not easily answered. It seems, however, that Judaism has an approach to looking at the problem. Let me explain. I have been involved in cases where congregants have someone in their family facing death. One traditional response to such a dire situation is to change the name of the person in a life-threatening situation. By doing so, we create an alternative ending, namely, life instead of death. I asked one of my Torah teachers how this works, and this is what he told me. A number of years ago, drugs were discovered in the locker of a student in our high school. The school had a zero tolerance policy, which mandated immediate expulsion for the offending student. The parents appealed for a second chance, arguing that their child would be lost Jewishly if she were to leave a Jewish day school. I understood what was at stake, but I could not sacrifice the wellbeing of the many for the good of one.

A number of years ago, drugs were discovered in the locker of a student in our high school. The school had a zero tolerance policy, which mandated immediate expulsion for the offending student. The parents appealed for a second chance, arguing that their child would be lost Jewishly if she were to leave a Jewish day school. I understood what was at stake, but I could not sacrifice the wellbeing of the many for the good of one. In 1976, I considered taking a rabbinic post in a Modern Orthodox synagogue that was located in a Hasidic community in New York. It would mean that my kids would attend a Hasidic Jewish day school with a minimalist curriculum of secular studies. Ultimately the job was not offered to me, but I had no hesitation about taking the position even if it meant my kids would attend a school that was not necessarily in sync with the way I practiced my Judaism. I reasoned that whatever the approach of the school, I would balance my children’s education with my own parental perspective on things and my kids would turn out fine. Of course, it was only a hypothesis, but it made sense to me at the time. Watching One of Us made me wonder if in 1976 I was overly naïve about the consequences of an education devoid of serious secular studies.

In 1976, I considered taking a rabbinic post in a Modern Orthodox synagogue that was located in a Hasidic community in New York. It would mean that my kids would attend a Hasidic Jewish day school with a minimalist curriculum of secular studies. Ultimately the job was not offered to me, but I had no hesitation about taking the position even if it meant my kids would attend a school that was not necessarily in sync with the way I practiced my Judaism. I reasoned that whatever the approach of the school, I would balance my children’s education with my own parental perspective on things and my kids would turn out fine. Of course, it was only a hypothesis, but it made sense to me at the time. Watching One of Us made me wonder if in 1976 I was overly naïve about the consequences of an education devoid of serious secular studies. I remember hearing about the incident. I learned that two young boys were playing around with each other and one of them had a stick with a nail on the end of it. In the course of their “playing around,” the boy with the stick hit the other child in the eye. Blood gushed out and the boy was in great pain.

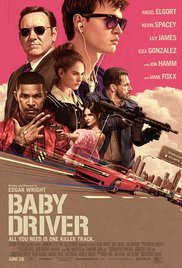

I remember hearing about the incident. I learned that two young boys were playing around with each other and one of them had a stick with a nail on the end of it. In the course of their “playing around,” the boy with the stick hit the other child in the eye. Blood gushed out and the boy was in great pain. I watched this film at a time when the US is in the midst of a major debate over its immigration program. One side views immigrants who came here illegally as potentially dangerous and argues for tighter border controls. The other side sees illegal immigrants as a positive force in the US who make important contributions to America and who simply want a better life for themselves and their children.

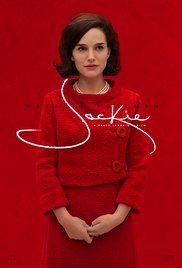

I watched this film at a time when the US is in the midst of a major debate over its immigration program. One side views immigrants who came here illegally as potentially dangerous and argues for tighter border controls. The other side sees illegal immigrants as a positive force in the US who make important contributions to America and who simply want a better life for themselves and their children. Everyone my age remembers where they were when we heard the news that President Kennedy was shot and killed. I was in Mt. Vernon, New York, driving in the center of the town with my mother. The radio program to which we were listening abruptly stopped and they announced the president’s death. All the cars, including mine, halted. No one could move. My mother began crying. No one ever imagined such a tragedy happening. That fateful day and the days following are portrayed in Jackie, a thoughtful and eerie film that imagines the tragedy through the eyes and emotions of Jackie, the first lady.

Everyone my age remembers where they were when we heard the news that President Kennedy was shot and killed. I was in Mt. Vernon, New York, driving in the center of the town with my mother. The radio program to which we were listening abruptly stopped and they announced the president’s death. All the cars, including mine, halted. No one could move. My mother began crying. No one ever imagined such a tragedy happening. That fateful day and the days following are portrayed in Jackie, a thoughtful and eerie film that imagines the tragedy through the eyes and emotions of Jackie, the first lady. A number of years ago, I engaged a contractor to build an addition onto my home. Over the course of several months, he would ask me for an advance on his fee because he needed to buy supplies and pay his workers. I had no experience dealing with contractors and assumed everyone was honest, so whenever he asked for money I gave it to him.

A number of years ago, I engaged a contractor to build an addition onto my home. Over the course of several months, he would ask me for an advance on his fee because he needed to buy supplies and pay his workers. I had no experience dealing with contractors and assumed everyone was honest, so whenever he asked for money I gave it to him. When I was in fourth grade in elementary school, I encountered long division. Until then I never had a problem with mathematics, but I had a rude awakening. I had trouble mastering it, and my inability to attain instant success in the subject forever prejudiced my attitude towards math, so much so that when I entered college I chose my major field of study based upon the major not requiring any math courses. I realized as I went through high school that I had no gift for mathematics.

When I was in fourth grade in elementary school, I encountered long division. Until then I never had a problem with mathematics, but I had a rude awakening. I had trouble mastering it, and my inability to attain instant success in the subject forever prejudiced my attitude towards math, so much so that when I entered college I chose my major field of study based upon the major not requiring any math courses. I realized as I went through high school that I had no gift for mathematics.