An essential challenge in the life of administrators is to decide issues based upon whether something is good for the many or only good for the few. I confronted this often as a school principal. In my early years on the job, I made exceptions to the general rule because I wanted to do what was best for the individual child, and also because I was interested in boosting enrollment for what was then an unknown and untested institution. Having a large enrollment was outwardly a sign of success and it meant more tuition dollars to support the school’s programs.

An essential challenge in the life of administrators is to decide issues based upon whether something is good for the many or only good for the few. I confronted this often as a school principal. In my early years on the job, I made exceptions to the general rule because I wanted to do what was best for the individual child, and also because I was interested in boosting enrollment for what was then an unknown and untested institution. Having a large enrollment was outwardly a sign of success and it meant more tuition dollars to support the school’s programs.

As I matured in my profession, I made less and less exceptions because every exception undermined the overall policies of the school. Once the enrollment stabilized, I could set higher behavioral and academic standards that, in the long run, made the school stronger educationally.

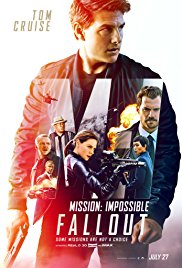

Ethan Hunt, leader of the Mission Impossible (MI6) team of heroes, faces similar challenges in Mission Impossible – Fallout, the latest installment in what has become one of the great action movie franchises in film history. In the course of his mission, Ethan frequently has to decide whether to save the world or an individual friend, who has time and again saved his life and the lives of others.

Ethan’s task in this story is to recover three plutonium cores that have found their way into the hands of terrorists. When he is about to take possession of the plutonium, he discovers that the villains have captured Luther Stickell, one of the members of Ethan’s group. Ethan has a choice: to take possession of the plutonium, which can be used for atomic weapons to destroy the world, or to save his friend Luther. He opts for the latter, and thus begins a worldwide search to find the plutonium and to eliminate the terrorists. His task takes him to Paris, Berlin, London, and an assortment of exotic locations in which Ethan fights for his life as well as for possession of the plutonium cores.

Mission Impossible is a movie in which we know the outcome. Even If Ethan makes a questionable decision, things will work out okay in the end and the world will be saved. Nonetheless, the film presents the dilemma of making a choice knowing that the result will most likely lead to an imperfect solution.

In The Ethics of the Fathers the Sages ask: “Who is wise?” They respond: “One who sees the future.” In truth, one cannot foresee the future, but one can predict a likely outcome. Rabbi Bernie Fox shares an innovative twist on how the Rabbis of the Talmud viewed a wise man: ”Our Sages did not regard a person as wise simply as a consequence of the accumulation of data. A wise person is an individual who is guided by wisdom. This means that the reality of ideas is as definite to the wise person as input received through the senses. The Sages characterized this quality by referring to seeing the future. The future, although only an idea, is as real as the present that is seen through the senses.”

Ethan Hunt is a wise man and knows the likely outcome of saving his friend rather than rescuing the world; but when it comes to saving human life, especially that of a friend, he is conflicted. He knows terrorists are bent on destroying world order and are prepared to eradicate anyone who stands in their way. In spite of this, Ethan does not abandon his humanity.

In the imaginary world of Mission Impossible – Fallout, Ethan understands the dire consequences of saving his friend over securing the plutonium. We, the audience, know that Ethan will save his friend and also save the world. He will destroy the enemy and, at the same time, affirm his concern for the value of one single life, and that is why we admire him. The Talmud expresses this message, embedded in the mind and heart of Ethan Hunt: “he who saves a single life saves the entire world.”

I know people who are very busy in their professional careers, but who always find time for family, and especially their children. One rabbi friend of mine who works for a number of companies in the pension fund industry in order to make a living for his large family always finds time to study Torah with his children. It is a weekly commitment that he rarely misses, and I admire him greatly. That kind of devotion to family is absent in the life of Austrian mountain climber Heinrich Harrer in Seven Years in Tibet, a picturesque drama that chronicles his life before, during, and after World War II.

I know people who are very busy in their professional careers, but who always find time for family, and especially their children. One rabbi friend of mine who works for a number of companies in the pension fund industry in order to make a living for his large family always finds time to study Torah with his children. It is a weekly commitment that he rarely misses, and I admire him greatly. That kind of devotion to family is absent in the life of Austrian mountain climber Heinrich Harrer in Seven Years in Tibet, a picturesque drama that chronicles his life before, during, and after World War II. A friend of mine recently told me that, during his senior year at high school, he was caught by his History teacher for plagiarizing a term paper. It turns out that he copied the paper from his sister who, a number of years earlier, had submitted the paper to a different teacher at the same high school and she received an “A.”

A friend of mine recently told me that, during his senior year at high school, he was caught by his History teacher for plagiarizing a term paper. It turns out that he copied the paper from his sister who, a number of years earlier, had submitted the paper to a different teacher at the same high school and she received an “A.” I have been having a problem finding films to review that by any definition I can call “kosher.” So much of what is on the screen today is full of unsavory behaviors that I have difficulty recommending them. Indeed, I rarely go to the cinema in Israel. I order movies on Amazon when they become reasonably priced and then send them to my daughter in Lakewood, New Jersey. When I visit the US, I then pick them up and bring them back to Israel where I can watch them at home.

I have been having a problem finding films to review that by any definition I can call “kosher.” So much of what is on the screen today is full of unsavory behaviors that I have difficulty recommending them. Indeed, I rarely go to the cinema in Israel. I order movies on Amazon when they become reasonably priced and then send them to my daughter in Lakewood, New Jersey. When I visit the US, I then pick them up and bring them back to Israel where I can watch them at home. There is a statement in The Ethics of the Fathers that resonates with me every time I read it: “civility (or good behavior) comes before Torah.” What is the takeaway? That for the Torah to reside in a person, he first has to conduct himself like a mentsch.

There is a statement in The Ethics of the Fathers that resonates with me every time I read it: “civility (or good behavior) comes before Torah.” What is the takeaway? That for the Torah to reside in a person, he first has to conduct himself like a mentsch. After serving in Jewish education for many years in America and teaching in two schools in Israel, I am no longer active in the field of education. However, I continue to read articles about the latest trends in Jewish education, particularly at the high school level where I spent most of my career.

After serving in Jewish education for many years in America and teaching in two schools in Israel, I am no longer active in the field of education. However, I continue to read articles about the latest trends in Jewish education, particularly at the high school level where I spent most of my career. I first saw Lawrence of Arabia in 1962. It was a cinematic event, panoramic in scope and intellectually engaging. The central character, T. E. Lawrence, a brave and psychologically complex British lieutenant, was not a conventional movie hero and the story was complicated. I remember being impressed by the dramatic visuals, but I was not touched emotionally by the narrative.

I first saw Lawrence of Arabia in 1962. It was a cinematic event, panoramic in scope and intellectually engaging. The central character, T. E. Lawrence, a brave and psychologically complex British lieutenant, was not a conventional movie hero and the story was complicated. I remember being impressed by the dramatic visuals, but I was not touched emotionally by the narrative. A friend of mine scheduled hip replacement surgery. He and his wife visited the surgeon who had been recommended by many. After the meeting, my friend and his wife came away with different impressions. While both felt the surgeon was highly competent, the wife detected a streak of arrogance in the doctor, and it bothered her. She preferred a surgeon who radiated humility, not pride. The husband felt that, at the end of the day, God is the healer, not the surgeon, and the surgeon’s arrogant attitude was not a reason to choose another doctor.

A friend of mine scheduled hip replacement surgery. He and his wife visited the surgeon who had been recommended by many. After the meeting, my friend and his wife came away with different impressions. While both felt the surgeon was highly competent, the wife detected a streak of arrogance in the doctor, and it bothered her. She preferred a surgeon who radiated humility, not pride. The husband felt that, at the end of the day, God is the healer, not the surgeon, and the surgeon’s arrogant attitude was not a reason to choose another doctor. My parents were not social butterflies. They had many friends because they were good friends to others. They were people who always kept their word and always were there to help relatives and friends during the hard times. For me, they were role models of reliability and champions of kindness. They were the friends upon whom you could count, and that notion of friendship was absorbed by me.

My parents were not social butterflies. They had many friends because they were good friends to others. They were people who always kept their word and always were there to help relatives and friends during the hard times. For me, they were role models of reliability and champions of kindness. They were the friends upon whom you could count, and that notion of friendship was absorbed by me. A friend of mine was recently given the opportunity to move to a better paying position in his company if he would relocate to the West Coast. He had just bought a home in Westchester and had planned to stay in the Northeast for the foreseeable future. But then this “once-in-a-lifetime” chance at improving his financial bottom line presented itself and for a few moments he was in a quandary.

A friend of mine was recently given the opportunity to move to a better paying position in his company if he would relocate to the West Coast. He had just bought a home in Westchester and had planned to stay in the Northeast for the foreseeable future. But then this “once-in-a-lifetime” chance at improving his financial bottom line presented itself and for a few moments he was in a quandary.