I taught an eighth grade class for a number of years in an ultra-Orthodox Jewish school in Israel. The secular class began in late afternoon and there were only two hours per week devoted to English language study.

I taught an eighth grade class for a number of years in an ultra-Orthodox Jewish school in Israel. The secular class began in late afternoon and there were only two hours per week devoted to English language study.

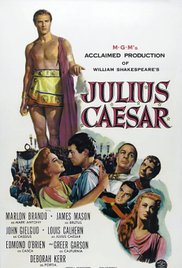

However, I still wanted to introduce the students to classic literature, and so I created a unit on Shakespeare in which the students read and acted out a few seminal scenes from the great bard’s plays. Included was the assassination scene in Julius Caesar. The kids had fun wearing makeshift togas and learned about something about the wielding of political power. Moreover, we reviewed some of the classic lines in the play in their context.

This cinematic version of Julius Caesar still has legs although it was filmed in black and white over sixty years ago. The reason: the stellar cast which included Marlon Brando as Marc Antony, James Mason as Brutus, and John Gielgud as Cassius.

The story begins in Rome when Caesar is at the height of his power. Some, however, see his rise to power as a reflection of his unflinching ambition and as a threat to Rome. They recruit the honorable Brutus to join with them in a plot to murder Caesar and, by doing so, save Rome. Brutus’ participation gives the conspirators respectability and the courage to move forward with their plans.

After the assassination, Brutus gives permission for Antony to eulogize Caesar, and his emotional speech turns the crowd against the conspirators. His funeral oration beginning with the famous words “Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears” is a speech for the ages, and Brando executes it in iconic fashion. This sets the stage for war between Antony and Brutus and their respective constituencies.

When I discussed the themes of the play with the students, I inwardly lamented their lack of exposure to great literature, the touchstone of superior culture. Of course, I understood that Torah study was primary, but one can still learn from great literature and the study of the humanities in general. Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein, a rabbinic scholar with a PhD in English from Harvard, writes that the humanities gives us insight into the human soul: “Great literature presents either a rendering, factual or imaginative, of aspects of the human condition, or a record of the artist’s grappling with the ultimate questions of human existence: man’s relation to himself, to others, to the cosmos, and above all to God.” As such, reading exceptional works of literature can help us navigate our own lives.

There are lines in Julius Caesar that express truths about life in a poetic way that touch the heart as well as the mind. Moreover, they coincide with Jewish sensibilities. Here is one of them: “Cowards die many times before their death, the valiant never taste of death but once.” This passage makes us think about how to confront fear. Another passage: “There is a tide in the affairs of men/ Which taken at the flood leads on to fortune/ Omitted, all the voyage of their life/ Is bound in shallows and miseries/ On such a full sea as we are now afloat/ And we must take the current when it serves/ Or lose our ventures.” The message here is to take advantage of the moment. Evaluate the present and then act boldly to determine your future.

What I found in instructing students of all ages is that life lessons that were embedded in sacred Jewish texts often emerged in the secular texts I was teaching in my English literature classes. My students, many of whom were not reared in observant Jewish homes, connected with the secular source more easily than with the sacred. In teaching, I understood that when it comes to student learning “the readiness is all.”

I enjoy and respect the company of people of faith, as long as they are not functioning as missionaries. Let me give you an example. When I was principal of a Jewish high school, I learned that one of our very fine Jewish general studies instructors was living with someone other than his wife. It was a private matter until I discovered he was hiring our students as babysitters for his paramour. At that point, I asked myself: if I were a parent, would I want my child to be exposed to a situation which was contrary to my own value system by a teacher in a school that shared my value system. Flash forward to another teacher in the school, the Christian mother of five children who was an outstanding science teacher. In her spare time, she wrote poetry about the details of God’s creation and always emphasized the renewal of God’s sustaining powers on each day of a person’s life, a message very much consistent with the ethos of our Jewish day school.

I enjoy and respect the company of people of faith, as long as they are not functioning as missionaries. Let me give you an example. When I was principal of a Jewish high school, I learned that one of our very fine Jewish general studies instructors was living with someone other than his wife. It was a private matter until I discovered he was hiring our students as babysitters for his paramour. At that point, I asked myself: if I were a parent, would I want my child to be exposed to a situation which was contrary to my own value system by a teacher in a school that shared my value system. Flash forward to another teacher in the school, the Christian mother of five children who was an outstanding science teacher. In her spare time, she wrote poetry about the details of God’s creation and always emphasized the renewal of God’s sustaining powers on each day of a person’s life, a message very much consistent with the ethos of our Jewish day school. My son-in-law is a special education educator focusing on autistic students. He helps kids and their families cope with a disability that manifests itself in different ways depending upon many idiosyncratic factors such as age and family background. Therapies that work in one situation may not work in another.

My son-in-law is a special education educator focusing on autistic students. He helps kids and their families cope with a disability that manifests itself in different ways depending upon many idiosyncratic factors such as age and family background. Therapies that work in one situation may not work in another. My oldest son, Rabbi Daniel, has recently written a book entitled What Will They Say About You When You Are Gone: Creating a Life of Legacy. Much of the book emerges from eulogies that he has delivered during the past 25 years as a synagogue rabbi. A consistent theme over the years is the good that people do anonymously, without any recognition or fanfare. Such good deeds done, below the societal radar, testify to the essential goodness of the deceased. Doing good without being recognized for it is at the heart of The Incredibles, an imaginative animated film that deals with superheroes who want to do good without receiving accolades. They just want to be helpful and do the right thing.

My oldest son, Rabbi Daniel, has recently written a book entitled What Will They Say About You When You Are Gone: Creating a Life of Legacy. Much of the book emerges from eulogies that he has delivered during the past 25 years as a synagogue rabbi. A consistent theme over the years is the good that people do anonymously, without any recognition or fanfare. Such good deeds done, below the societal radar, testify to the essential goodness of the deceased. Doing good without being recognized for it is at the heart of The Incredibles, an imaginative animated film that deals with superheroes who want to do good without receiving accolades. They just want to be helpful and do the right thing. In one of the Israeli schools in which I taught, the students in one particular seventh grade class were mostly interested in parroting back information. The typical question I received was “can I read the next paragraph” or “what was my grade on the last test?” It was rare to hear a question that reflected a thinking, active intellect.

In one of the Israeli schools in which I taught, the students in one particular seventh grade class were mostly interested in parroting back information. The typical question I received was “can I read the next paragraph” or “what was my grade on the last test?” It was rare to hear a question that reflected a thinking, active intellect. A “lone soldier” home is located around the corner from me. What is a “lone soldier?” He is a volunteer who serves in the Israel Defense Forces even though he has no immediate family with him or her in Israel. Reliable sources tell us there are over 6000 of them serving in the army.

A “lone soldier” home is located around the corner from me. What is a “lone soldier?” He is a volunteer who serves in the Israel Defense Forces even though he has no immediate family with him or her in Israel. Reliable sources tell us there are over 6000 of them serving in the army. For the past several years, I have been teaching in a middle school and a high school in Israel. I have observed that in dealing with 7th and 8th graders, the students tend to be very self-absorbed, interested only in what they have to say and not paying attention to the comments of others. In the high school, I see students more respectful of each other, more willing to listen to the opinions of a peer. There I see more students sensitive to the Biblical notion of “loving your neighbor as yourself.” Just as you would want to be heard, so too should you listen to the words of your neighbor and give his comments respect even when you disagree with him.

For the past several years, I have been teaching in a middle school and a high school in Israel. I have observed that in dealing with 7th and 8th graders, the students tend to be very self-absorbed, interested only in what they have to say and not paying attention to the comments of others. In the high school, I see students more respectful of each other, more willing to listen to the opinions of a peer. There I see more students sensitive to the Biblical notion of “loving your neighbor as yourself.” Just as you would want to be heard, so too should you listen to the words of your neighbor and give his comments respect even when you disagree with him. On rare occasions, I have been confronted with having to make a decision knowing that if I decide one way, I will hurt someone I care about; and if I decide differently, I will hurt someone else. Either way, I will wind up alienating a friend.

On rare occasions, I have been confronted with having to make a decision knowing that if I decide one way, I will hurt someone I care about; and if I decide differently, I will hurt someone else. Either way, I will wind up alienating a friend. I began my doctoral studies in English in Atlanta in 1972. It was intended to be a 5-year program, but it took much longer because I was busy with earning a living and rearing a young family. I finally received my PhD in 1984, twelve years after I started.

I began my doctoral studies in English in Atlanta in 1972. It was intended to be a 5-year program, but it took much longer because I was busy with earning a living and rearing a young family. I finally received my PhD in 1984, twelve years after I started. I live in Israel where I often read about the moral dilemmas faced by the Israel Defense Forces as they fight terror that threatens the fabric of daily life. There are no simple answers to these complex questions. I reflected on this reality as I watched Sicario, a tense and unsettling look on law enforcement in America as it tries to control illegal drug trafficking in Mexico, a drug trade that infiltrates the southern border of the United States.

I live in Israel where I often read about the moral dilemmas faced by the Israel Defense Forces as they fight terror that threatens the fabric of daily life. There are no simple answers to these complex questions. I reflected on this reality as I watched Sicario, a tense and unsettling look on law enforcement in America as it tries to control illegal drug trafficking in Mexico, a drug trade that infiltrates the southern border of the United States.