My oldest son, Rabbi Daniel, has recently written a book entitled What Will They Say About You When You Are Gone: Creating a Life of Legacy. Much of the book emerges from eulogies that he has delivered during the past 25 years as a synagogue rabbi. A consistent theme over the years is the good that people do anonymously, without any recognition or fanfare. Such good deeds done, below the societal radar, testify to the essential goodness of the deceased. Doing good without being recognized for it is at the heart of The Incredibles, an imaginative animated film that deals with superheroes who want to do good without receiving accolades. They just want to be helpful and do the right thing.

My oldest son, Rabbi Daniel, has recently written a book entitled What Will They Say About You When You Are Gone: Creating a Life of Legacy. Much of the book emerges from eulogies that he has delivered during the past 25 years as a synagogue rabbi. A consistent theme over the years is the good that people do anonymously, without any recognition or fanfare. Such good deeds done, below the societal radar, testify to the essential goodness of the deceased. Doing good without being recognized for it is at the heart of The Incredibles, an imaginative animated film that deals with superheroes who want to do good without receiving accolades. They just want to be helpful and do the right thing.

The main superheroes in the film are Mr. Incredible, who possesses super strength, Elastigirl, who can stretch her body like flexible rubber, and Frozone, who has the ability to create ice instantly. The opening scenes depict the heroes in a series of events where they are called upon to use their superpowers to catch criminals. They are almost entirely successful except in one case when they are foiled by Buddy, an enthusiastic fan of Mr. Incredible, who wants to be his ward like Batman’s Robin. It is his interruption that prevents Mr. Incredible from capturing the culprit.

After the excitement, the superheroes return to their alter egos and lead normal lives. Mr. Incredible is Robert Parr, Elastigirl is is Helen Parr, Robert’s wife, and Frozone is Lucius Best, Parr’s close friend.

Their lives are turned upside down when an avalanche of lawsuits are filed against the superheroes because of civilian injuries and collateral damage. Eventually, the superheroes conclude that they have to turn in their super suits and live normal lives away from the limelight, and assume their secret identities permanently. The Superhero Relocation Program provides ex-superheroes with new jobs and homes and amnesty for past actions.

The narrative continues 15 years later with Robert working for an insurance company, leading a life focused on his wife and children. However, he still dreams of his superhero years when he saved many people from disaster.

Soon an opportunity arises for him to return to his calling as a superhero. For a hefty sum, he is asked by Mirage, a mysterious woman, to destroy a rogue robot who is wreaking havoc on the residents of a remote island. However, Mr. Incredible soon discovers that his job is a ruse simply to get him to the island where Mirage’s anonymous employer terminates the lives of all the existing superheroes. The race to save himself and other superheroes makes for a tense and exciting denouement, in which Elastigirl, Frozone, and Mr. Incredible’s children play key roles.

A character trait that stands out among all three superheroes is their lack of interest in public acclaim. None of them is seeking recognition of any kind. They only want to help other people. This is a Jewish sensibility. In The Ethics of the Fathers, Jews are instructed to serve God, to do the right thing, without any intention of receiving reward. Moreover, Maimonides, in describing the eight levels of charity, writes that giving anonymously is one of the highest forms of charity.

It is significant to note that Mr. Incredible’s adversary is motivated primarily by a strong desire for recognition. He purposely destabilizes the world so that he can arrive on the scene and put it back together again in front of a large audience. He is a villain who thrives on the aphrodisiac of fame. The Incredibles reminds us that doing good things is more enduring than transient fame.

In the course of my career, I have occasionally met people who are morally inconsistent. One example comes to mind. He was a synagogue attendee and very charitable towards the institutions I represented, but he gained his wealth by selling drugs, a fact I only learned some time after my friend was incarcerated. Jewish law is very clear: you cannot accomplish a good deed by committing an immoral action. However, in the woof and warp of daily life, many people make ethical compromises to justify an affluent lifestyle and the good deeds that one performs through charitable giving.

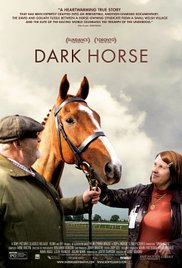

In the course of my career, I have occasionally met people who are morally inconsistent. One example comes to mind. He was a synagogue attendee and very charitable towards the institutions I represented, but he gained his wealth by selling drugs, a fact I only learned some time after my friend was incarcerated. Jewish law is very clear: you cannot accomplish a good deed by committing an immoral action. However, in the woof and warp of daily life, many people make ethical compromises to justify an affluent lifestyle and the good deeds that one performs through charitable giving. Dark Horse is a horse story, but, in my book, a horse story is always a human story. In the case of Dark Horse, it is a documentary about a barmaid, Jan Vokes, in Wales who decides to breed a racehorse. She enlists the aid of other villagers for advice and to raise the money to breed a champion racehorse. The simple folk who help Jan are not interested in monetary rewards, although they would welcome them. What drives them is friendship and the desire to do something extraordinary that will forever be worthy of remembrance.

Dark Horse is a horse story, but, in my book, a horse story is always a human story. In the case of Dark Horse, it is a documentary about a barmaid, Jan Vokes, in Wales who decides to breed a racehorse. She enlists the aid of other villagers for advice and to raise the money to breed a champion racehorse. The simple folk who help Jan are not interested in monetary rewards, although they would welcome them. What drives them is friendship and the desire to do something extraordinary that will forever be worthy of remembrance. There often is a price paid for celebrity, especially for family members. I read of Hollywood movie stars who have dysfunctional kids getting into all sorts of trouble and trafficking in drugs.

There often is a price paid for celebrity, especially for family members. I read of Hollywood movie stars who have dysfunctional kids getting into all sorts of trouble and trafficking in drugs. When I was in eighth grade, I invited Dolly, a girl I knew through my local JCC, to my junior high school. I wanted to show her the building in which I took great pride. I had nothing in mind other than to show her my classrooms, but my visit after the school’s regular hours caught the attention of the school janitor who reported my unconventional visit to the principal. The next day I was summoned to his office and given a reprimand for escorting Dolly by myself after school. What I did was give the appearance of impropriety, and the incident gave me a visceral awareness of how appearances can often telegraph the wrong message about a person or event.

When I was in eighth grade, I invited Dolly, a girl I knew through my local JCC, to my junior high school. I wanted to show her the building in which I took great pride. I had nothing in mind other than to show her my classrooms, but my visit after the school’s regular hours caught the attention of the school janitor who reported my unconventional visit to the principal. The next day I was summoned to his office and given a reprimand for escorting Dolly by myself after school. What I did was give the appearance of impropriety, and the incident gave me a visceral awareness of how appearances can often telegraph the wrong message about a person or event. As an educator for many years, I have encountered parents who opt for home schooling instead of enrolling their children into a traditional school. Sometimes the motive of the parent is to save the cost of private school tuition; at other times parents truly feel that conventional schools are often inferior and do not sufficiently tap a child’s intellectual potential. For these parents, home schooling offers an alternative and parents begin enthusiastically to educate their own kids at home.

As an educator for many years, I have encountered parents who opt for home schooling instead of enrolling their children into a traditional school. Sometimes the motive of the parent is to save the cost of private school tuition; at other times parents truly feel that conventional schools are often inferior and do not sufficiently tap a child’s intellectual potential. For these parents, home schooling offers an alternative and parents begin enthusiastically to educate their own kids at home. There is a story in the Talmud about a sage, Rabbi Elazar, who made disparaging remarks about an ugly man, whereupon the ugly man said that he was created ugly by God and that was his lot through no fault of his own. The sage regretted the unkind words he said and an overwhelming sense of remorse plagued him. The sage died soon thereafter.

There is a story in the Talmud about a sage, Rabbi Elazar, who made disparaging remarks about an ugly man, whereupon the ugly man said that he was created ugly by God and that was his lot through no fault of his own. The sage regretted the unkind words he said and an overwhelming sense of remorse plagued him. The sage died soon thereafter. As a child with a Downs Syndrome sister, I recall in the 1950s families with Downs Syndrome children often kept their kids in the proverbial closet. My mother and father thought differently. They felt Carol, their daughter, needed to be visible in the community and that the community should provide the resources for such kids to develop their potential to the fullest extent possible. That’s why my mother fought for the establishment for a school in Westchester County for the mentally retarded and, when Carol was older, for the establishment of a retarded children’s workshop in White Plains so that Carol could feel and be productive in her mature years.

As a child with a Downs Syndrome sister, I recall in the 1950s families with Downs Syndrome children often kept their kids in the proverbial closet. My mother and father thought differently. They felt Carol, their daughter, needed to be visible in the community and that the community should provide the resources for such kids to develop their potential to the fullest extent possible. That’s why my mother fought for the establishment for a school in Westchester County for the mentally retarded and, when Carol was older, for the establishment of a retarded children’s workshop in White Plains so that Carol could feel and be productive in her mature years. During my entire professional career, I used a PC both at home and the office. The Apple computer seemed geared for geeks and not suitable for an office environment. But as it happens with all machines, eventually they break and it was time to buy a new computer. I consulted my son, Benyamin, and he encouraged me to buy the iMac. Now that I was not working in a school office and had more flexible work hours, I decided to seriously consider the Apple. After several months of indecision, I finally bought one.

During my entire professional career, I used a PC both at home and the office. The Apple computer seemed geared for geeks and not suitable for an office environment. But as it happens with all machines, eventually they break and it was time to buy a new computer. I consulted my son, Benyamin, and he encouraged me to buy the iMac. Now that I was not working in a school office and had more flexible work hours, I decided to seriously consider the Apple. After several months of indecision, I finally bought one. House of Sand and Fog may be the saddest film I have ever seen. It demonstrates the tragic consequences of failed communication, when two people are, metaphorically speaking, on opposite sides of the table unable to find a compromise middle ground before it is too late to avoid catastrophe.

House of Sand and Fog may be the saddest film I have ever seen. It demonstrates the tragic consequences of failed communication, when two people are, metaphorically speaking, on opposite sides of the table unable to find a compromise middle ground before it is too late to avoid catastrophe.