My granddaughter, Shoshi, is a very talented pianist. Not only does she play well, she also composes some of her own compositions. Whenever I am in the States and visiting Shoshi and the rest of her family, I ask her to play some of her own melodies. Hearing them is a pleasure and the music relaxes me. Life without music seems sterile; with music, it is vibrant.

Music occupies a very special place in cinema. Sometimes it is critically important because it underscores major themes in the film you are watching. It is the soul of the movie, part of the creative vision of the director and actors who want to convey the meaning of a film to those who see it. It is not just filler; rather it is essential to the creative film experience.

One of my first exposures to the power of music in the cinema was watching Chariots of Fire, the 1981 Academy Award winning film about racing. It begins with a scene of men running along the English beach preparing for the 1924 Olympics. The camera depicts in slow-motion the men running; the music in the background, composed by Vangelis, is transcendent and uplifting.

Score is a documentary that describes the history of motion picture scoring. It begins with a discussion of silent films. In truth, they were not really silent because an organist often played during the film to highlight and punctuate the action on the screen. The game-changer in movie soundtrack history was Max Steiner’s score for King Kong in 1933. The music transformed a standard special-effects monster movie into a total cinematic experience.

After this brief historical introduction, the film explores the creative processes of a number of composers whose work in films helped make the films memorable. They include such musical luminaries as John Williams, Hans Zimmer, Danny Elfman, and Ennio Morricone.

Some soundtracks still remain with us after many years. They include such classics as The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, Jaws, Jurassic Park, Star Wars, The Magnificent Seven, and Titanic. Just listening to the music conjures up images and emotions from the past.

What is fascinating is the technology and new musical genres that influence contemporary soundtracks. Innovation in sound is a hallmark of famous iconoclastic films. The composer does not limit himself to traditional orchestral instruments. Nature sounds and instruments of primitive cultures often substitute for conventional background music to accentuate what is happening on the screen.

Jewish tradition has much to say about the interplay of music, life, and emotion. When the Jewish nation crosses the Red Sea, the people spontaneously break out in song. King David, the author of Psalms, is known in the Bible as the “sweet singer of Israel.” The priests sang in the Temple every day. Prayers are often sung, not merely recited.

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks writes: “There is an inner connection between music and the spirit. When language aspires to the transcendent and the soul longs to break free of the gravitational pull of the earth, it modulates into song. Tolstoy called it the shorthand of emotion. Words are the language of the mind. Music is the language of the soul.”

Score reminds us that dialogue in movies can take us only so far. The soundtrack, which is the last creative part of the film to be added, is crucial to the overall affect the film has on the viewer. So it is in Judaism. What enables Jewish tradition to pass from generation to generation are not simply the dry words of the Bible and Talmud, but rather the spirit, the music, through which it is transmitted. Song represents the soul within and the soul lives beyond the present.

In the news recently was a story about a politician who announced that he was not going to seek re-election. He was successful in his career and made lots of money giving speeches across the country. Why was he retiring? He said it was because he did not want to be a “weekend dad” to his teenage children. He understood that his kids needed more face time with him, and he did not want to look back at his life and regret not spending more time with his children. Family was more important to him than fame or wealth. This dilemma in broad outline is at the heart of The Greatest Showman, the story of the rise of P.T. Barnum who makes choices between family and the pursuit of personal goals.

In the news recently was a story about a politician who announced that he was not going to seek re-election. He was successful in his career and made lots of money giving speeches across the country. Why was he retiring? He said it was because he did not want to be a “weekend dad” to his teenage children. He understood that his kids needed more face time with him, and he did not want to look back at his life and regret not spending more time with his children. Family was more important to him than fame or wealth. This dilemma in broad outline is at the heart of The Greatest Showman, the story of the rise of P.T. Barnum who makes choices between family and the pursuit of personal goals. In the 1970s and beyond, Billy Joel was one of my favorite musical artists. At the start of his career, I had an opportunity to hear him in Atlanta, but I missed that chance. I finally saw him in concert at Madison Square Garden in New York in 2017; the show was one of those one-of-a-kind concerts that remains in your memory for a long time after. So it was with great anticipation that I watched The Last Play at the Shea, a 2010 documentary that recorded the 2008 Billy Joel concert that was the last concert at Shea Stadium, a huge sports venue that was scheduled for demolition the following year.

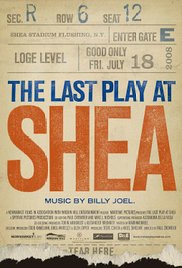

In the 1970s and beyond, Billy Joel was one of my favorite musical artists. At the start of his career, I had an opportunity to hear him in Atlanta, but I missed that chance. I finally saw him in concert at Madison Square Garden in New York in 2017; the show was one of those one-of-a-kind concerts that remains in your memory for a long time after. So it was with great anticipation that I watched The Last Play at the Shea, a 2010 documentary that recorded the 2008 Billy Joel concert that was the last concert at Shea Stadium, a huge sports venue that was scheduled for demolition the following year. There often is a price paid for celebrity, especially for family members. I read of Hollywood movie stars who have dysfunctional kids getting into all sorts of trouble and trafficking in drugs.

There often is a price paid for celebrity, especially for family members. I read of Hollywood movie stars who have dysfunctional kids getting into all sorts of trouble and trafficking in drugs. I live life as it unfolds in the present moment. I do not recall saying to myself “What if I had done this rather than that.” Yet I have friends who continually ask themselves “what would my life be like if I had made this decision rather than that decision.” The reality is that we cannot turn back the clock and decisions we made years ago cannot be changed. Those decisions affect our lives many years later.

I live life as it unfolds in the present moment. I do not recall saying to myself “What if I had done this rather than that.” Yet I have friends who continually ask themselves “what would my life be like if I had made this decision rather than that decision.” The reality is that we cannot turn back the clock and decisions we made years ago cannot be changed. Those decisions affect our lives many years later. A couple of years ago, a friend of mine was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease. I did not see him often, so it was unnerving for me to see him so helpless and confused when I finally visited him. Once a robust, intelligent, and expressive man, he was a shadow of his former self, needing almost 24- hour care. Now his family only had memories of the great man he once was.

A couple of years ago, a friend of mine was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease. I did not see him often, so it was unnerving for me to see him so helpless and confused when I finally visited him. Once a robust, intelligent, and expressive man, he was a shadow of his former self, needing almost 24- hour care. Now his family only had memories of the great man he once was. There is a brief scene in Beyond the Sea, a biopic of singer Bobby Darin, which resonates with me personally. Bobby unbuttons his shirt and reveals his scar from open-heart surgery. It looks like a long zipper on his chest. I, too, have had open-heart surgery and remember other patients telling me I am now a member of the “zipper club,” all of whose members brandish an extended scar on their chest.

There is a brief scene in Beyond the Sea, a biopic of singer Bobby Darin, which resonates with me personally. Bobby unbuttons his shirt and reveals his scar from open-heart surgery. It looks like a long zipper on his chest. I, too, have had open-heart surgery and remember other patients telling me I am now a member of the “zipper club,” all of whose members brandish an extended scar on their chest.