As I have gotten older, I have less and less interest in acquiring things. I remember that as a young man, I had a serious interest in cameras and in audio systems. I no longer possess such interests. I am guided by what the great Jewish Sages have said about how to conduct one’s life; namely, that the only thing we take with us to the after-life is our good deeds; and so I spend my time learning Torah, trying to make the world a better place through my writing both on the Internet and in books, and doing acts of kindness. This mindset made me very receptive to the inspiring documentary about Warren Buffet entitled Becoming Warren Buffet.

As I have gotten older, I have less and less interest in acquiring things. I remember that as a young man, I had a serious interest in cameras and in audio systems. I no longer possess such interests. I am guided by what the great Jewish Sages have said about how to conduct one’s life; namely, that the only thing we take with us to the after-life is our good deeds; and so I spend my time learning Torah, trying to make the world a better place through my writing both on the Internet and in books, and doing acts of kindness. This mindset made me very receptive to the inspiring documentary about Warren Buffet entitled Becoming Warren Buffet.

Warren Buffett is a billionaire, yet he does not live like one. He resides in a modest residence in Omaha where he was born and drives to work every day to his company Berkshire Hathaway, the fifth largest public company in the world. He is now 86 years old and still retains the energy and curiosity of a much younger man.

His ambition to become a millionaire began when he was a teenager. He sold papers and started to sell stocks not long after. He was very good at calculations and developed two important rules as he accumulated wealth: (1) never lose money and (2) never forget rule number 1.

Buffet was not guided by passing investment fads. He always looked for value. Ultimately, value will be recognized even if a stock at present seems not worth much. For that reason, he began his career searching for undervalued stocks that might one day be more valuable.

Most noteworthy is the fact that throughout his career he conducted himself with a deep sense of morality. If there ever were a conflict between monetary profit and retaining one’s good name, he chose to protect his good name and the integrity of his company. Here are three of his most famous quotes: (1) “We can afford to lose money – even a lot of money. But we can’t afford to lose reputation – even a shred of reputation. We must continue to measure every act against not only what is legal but also what we would be happy to have written about on the front page of a national newspaper in an article written by an unfriendly but intelligent reporter.” (2) “As a corollary, let me know promptly if there’s any significant bad news. I can handle bad news but I don’t like to deal with it after it has festered for a while. A reluctance to face up immediately to bad news is what turned a problem at Salomon from one that could have easily been disposed of into one that almost caused the demise of a firm with 8,000 employees.” (3) “Lose money for the firm, and I will be understanding. Lose a shred of reputation for the firm, and I will be ruthless.’”

As the film describes his boyhood and the powerful influence of his father among many others who shaped his future, we see how Buffet arrives at a point in life when all he wants to do is leave a legacy of good things for the future. He wants to make the world a better place, and allies himself with the foundation of Bill and Melinda Gates to make his largest ever charitable gift of nearly 2.8 billion dollars.

The Ethics of the Fathers, a classic of Jewish wisdom literature, tells us there are several ways to achieve spiritual greatness, but one way supersedes all others: “Rabbi Shimon used to say: There are three crowns–the crown of Torah, the crown of priesthood and the crown of sovereignty–but the crown of a good name surmounts them all.” The crown of Torah represents Jewish learning as a way to become holy. The crown of priesthood represents getting close to holiness through Temple service and prayer. The crown of sovereignty represents occupying public office, which enables you to improve the plight of your subjects. However, the crowning achievement is maintaining a good name, which represents being able navigate life in a way that brings credit to you and to God. Becoming Warren Buffet is a testament to the wisdom and satisfaction of leading a life that inspires and benefits the world around you.

My oldest son, Rabbi Daniel, has recently written a book entitled What Will They Say About You When You Are Gone: Creating a Life of Legacy. Much of the book emerges from eulogies that he has delivered during the past 25 years as a synagogue rabbi. A consistent theme over the years is the good that people do anonymously, without any recognition or fanfare. Such good deeds done, below the societal radar, testify to the essential goodness of the deceased. Doing good without being recognized for it is at the heart of The Incredibles, an imaginative animated film that deals with superheroes who want to do good without receiving accolades. They just want to be helpful and do the right thing.

My oldest son, Rabbi Daniel, has recently written a book entitled What Will They Say About You When You Are Gone: Creating a Life of Legacy. Much of the book emerges from eulogies that he has delivered during the past 25 years as a synagogue rabbi. A consistent theme over the years is the good that people do anonymously, without any recognition or fanfare. Such good deeds done, below the societal radar, testify to the essential goodness of the deceased. Doing good without being recognized for it is at the heart of The Incredibles, an imaginative animated film that deals with superheroes who want to do good without receiving accolades. They just want to be helpful and do the right thing. In the course of my career, I have occasionally met people who are morally inconsistent. One example comes to mind. He was a synagogue attendee and very charitable towards the institutions I represented, but he gained his wealth by selling drugs, a fact I only learned some time after my friend was incarcerated. Jewish law is very clear: you cannot accomplish a good deed by committing an immoral action. However, in the woof and warp of daily life, many people make ethical compromises to justify an affluent lifestyle and the good deeds that one performs through charitable giving.

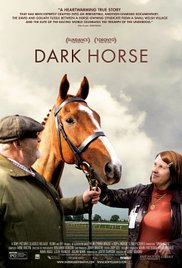

In the course of my career, I have occasionally met people who are morally inconsistent. One example comes to mind. He was a synagogue attendee and very charitable towards the institutions I represented, but he gained his wealth by selling drugs, a fact I only learned some time after my friend was incarcerated. Jewish law is very clear: you cannot accomplish a good deed by committing an immoral action. However, in the woof and warp of daily life, many people make ethical compromises to justify an affluent lifestyle and the good deeds that one performs through charitable giving. Dark Horse is a horse story, but, in my book, a horse story is always a human story. In the case of Dark Horse, it is a documentary about a barmaid, Jan Vokes, in Wales who decides to breed a racehorse. She enlists the aid of other villagers for advice and to raise the money to breed a champion racehorse. The simple folk who help Jan are not interested in monetary rewards, although they would welcome them. What drives them is friendship and the desire to do something extraordinary that will forever be worthy of remembrance.

Dark Horse is a horse story, but, in my book, a horse story is always a human story. In the case of Dark Horse, it is a documentary about a barmaid, Jan Vokes, in Wales who decides to breed a racehorse. She enlists the aid of other villagers for advice and to raise the money to breed a champion racehorse. The simple folk who help Jan are not interested in monetary rewards, although they would welcome them. What drives them is friendship and the desire to do something extraordinary that will forever be worthy of remembrance. There often is a price paid for celebrity, especially for family members. I read of Hollywood movie stars who have dysfunctional kids getting into all sorts of trouble and trafficking in drugs.

There often is a price paid for celebrity, especially for family members. I read of Hollywood movie stars who have dysfunctional kids getting into all sorts of trouble and trafficking in drugs. When I was in eighth grade, I invited Dolly, a girl I knew through my local JCC, to my junior high school. I wanted to show her the building in which I took great pride. I had nothing in mind other than to show her my classrooms, but my visit after the school’s regular hours caught the attention of the school janitor who reported my unconventional visit to the principal. The next day I was summoned to his office and given a reprimand for escorting Dolly by myself after school. What I did was give the appearance of impropriety, and the incident gave me a visceral awareness of how appearances can often telegraph the wrong message about a person or event.

When I was in eighth grade, I invited Dolly, a girl I knew through my local JCC, to my junior high school. I wanted to show her the building in which I took great pride. I had nothing in mind other than to show her my classrooms, but my visit after the school’s regular hours caught the attention of the school janitor who reported my unconventional visit to the principal. The next day I was summoned to his office and given a reprimand for escorting Dolly by myself after school. What I did was give the appearance of impropriety, and the incident gave me a visceral awareness of how appearances can often telegraph the wrong message about a person or event. As an educator for many years, I have encountered parents who opt for home schooling instead of enrolling their children into a traditional school. Sometimes the motive of the parent is to save the cost of private school tuition; at other times parents truly feel that conventional schools are often inferior and do not sufficiently tap a child’s intellectual potential. For these parents, home schooling offers an alternative and parents begin enthusiastically to educate their own kids at home.

As an educator for many years, I have encountered parents who opt for home schooling instead of enrolling their children into a traditional school. Sometimes the motive of the parent is to save the cost of private school tuition; at other times parents truly feel that conventional schools are often inferior and do not sufficiently tap a child’s intellectual potential. For these parents, home schooling offers an alternative and parents begin enthusiastically to educate their own kids at home. There is a story in the Talmud about a sage, Rabbi Elazar, who made disparaging remarks about an ugly man, whereupon the ugly man said that he was created ugly by God and that was his lot through no fault of his own. The sage regretted the unkind words he said and an overwhelming sense of remorse plagued him. The sage died soon thereafter.

There is a story in the Talmud about a sage, Rabbi Elazar, who made disparaging remarks about an ugly man, whereupon the ugly man said that he was created ugly by God and that was his lot through no fault of his own. The sage regretted the unkind words he said and an overwhelming sense of remorse plagued him. The sage died soon thereafter. As a child with a Downs Syndrome sister, I recall in the 1950s families with Downs Syndrome children often kept their kids in the proverbial closet. My mother and father thought differently. They felt Carol, their daughter, needed to be visible in the community and that the community should provide the resources for such kids to develop their potential to the fullest extent possible. That’s why my mother fought for the establishment for a school in Westchester County for the mentally retarded and, when Carol was older, for the establishment of a retarded children’s workshop in White Plains so that Carol could feel and be productive in her mature years.

As a child with a Downs Syndrome sister, I recall in the 1950s families with Downs Syndrome children often kept their kids in the proverbial closet. My mother and father thought differently. They felt Carol, their daughter, needed to be visible in the community and that the community should provide the resources for such kids to develop their potential to the fullest extent possible. That’s why my mother fought for the establishment for a school in Westchester County for the mentally retarded and, when Carol was older, for the establishment of a retarded children’s workshop in White Plains so that Carol could feel and be productive in her mature years. During my entire professional career, I used a PC both at home and the office. The Apple computer seemed geared for geeks and not suitable for an office environment. But as it happens with all machines, eventually they break and it was time to buy a new computer. I consulted my son, Benyamin, and he encouraged me to buy the iMac. Now that I was not working in a school office and had more flexible work hours, I decided to seriously consider the Apple. After several months of indecision, I finally bought one.

During my entire professional career, I used a PC both at home and the office. The Apple computer seemed geared for geeks and not suitable for an office environment. But as it happens with all machines, eventually they break and it was time to buy a new computer. I consulted my son, Benyamin, and he encouraged me to buy the iMac. Now that I was not working in a school office and had more flexible work hours, I decided to seriously consider the Apple. After several months of indecision, I finally bought one.