A number of years ago, drugs were discovered in the locker of a student in our high school. The school had a zero tolerance policy, which mandated immediate expulsion for the offending student. The parents appealed for a second chance, arguing that their child would be lost Jewishly if she were to leave a Jewish day school. I understood what was at stake, but I could not sacrifice the wellbeing of the many for the good of one.

A number of years ago, drugs were discovered in the locker of a student in our high school. The school had a zero tolerance policy, which mandated immediate expulsion for the offending student. The parents appealed for a second chance, arguing that their child would be lost Jewishly if she were to leave a Jewish day school. I understood what was at stake, but I could not sacrifice the wellbeing of the many for the good of one.

It was a painful decision. I tried to be very helpful in finding another school for the student, but it was clear to me that the parents in the school wanted their kids to be in a safe environment above all, and I could not equivocate on this issue. The good of the many had to prevail over the good of the one.

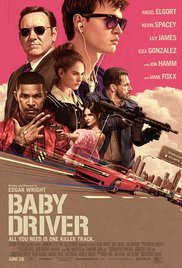

A similar dilemma presents itself in Jaws, the classic film about a killer shark that invades Amity Island, a New England tourist town that depends on vacationer dollars during the summer season. When a body is washed up on shore, Martin Brody, the local police chief, knows that it was the victim of a shark attack and wants to close the beaches. The mayor, however, fearing a major loss of tourist revenue, does not want the beaches closed and prevails on the authorities to list the fatality as a result of a boating accident. For the mayor, the good of the few, the local businessmen, outweighs the good of the many. It is not until two more people are killed does the mayor acknowledge the real threat of the shark.

Once the beaches are closed, Brody hires Quint, a local fisherman with experience killing sharks, to hunt the shark. Matt Hooper, a scientist from the Oceanographic Institute, joins the crew, bringing along an array of high-tech equipment including tracking devices, harpoons, scuba gear and tanks, and a supposed shark-proof steel cage.

Once out in the open waters in Quint’s vessel, the Orca, they lure the shark by tossing fish guts and blood around the boat. Eventually this attracts the great white shark. Quint harpoons it with a rope attached to a flotation barrel, but the shark pulls the barrel under the water and disappears under the boat, displaying an uncanny intelligence, which separates it from other sharks that Quint has hunted. There is an eerie suggestion that the shark knows the intention of the Orca’s crew and is determined to destroy them. A hair-raising finale ensues pitting brute force against skill, technology, and courage.

The debate between Martin Brody and the mayor about when to publicize the shark attack relates to the larger philosophic question of when to reveal potentially life-threatening information, a matter discussed in the codes of Jewish law. Generally, the determining factor is whether health and safety are at stake. If the information is needed to preserve life, then clearly it must be revealed immediately. If, however, the revealing of such information will possibly lead to the shortening of life, then it should be withheld. The classic example is the doctor telling a depressed patient that he has only a very brief time to live, and thus increasing his sense of despondency and decreasing his will to live.

In Jaws, the mayor has no such reasons to avoid telling the truth other than an economic one. In order to insure that the townspeople make great profits during the tourist season, he puts lives as risk. Such a financial motive is no justification for falsehoods. Jaws, indeed, is a cautionary tale about the folly of placing monetary gain over the absolute good of saving lives.

I remember hearing about the incident. I learned that two young boys were playing around with each other and one of them had a stick with a nail on the end of it. In the course of their “playing around,” the boy with the stick hit the other child in the eye. Blood gushed out and the boy was in great pain.

I remember hearing about the incident. I learned that two young boys were playing around with each other and one of them had a stick with a nail on the end of it. In the course of their “playing around,” the boy with the stick hit the other child in the eye. Blood gushed out and the boy was in great pain. One of the many things I enjoyed during my years of serving as principal of a high school was working with a top notch staff, a group of teachers who were mission-driven, focused on doing the best for their students. They were not limited by their job descriptions. I recall that, on several occasions, we needed someone to drive a van to pick up kids to come to school for several weeks. Teachers eagerly volunteered. They understood my dilemma and just did what was needed to get the task done. They did not simply stand on the side, waiting for someone else to do the job.

One of the many things I enjoyed during my years of serving as principal of a high school was working with a top notch staff, a group of teachers who were mission-driven, focused on doing the best for their students. They were not limited by their job descriptions. I recall that, on several occasions, we needed someone to drive a van to pick up kids to come to school for several weeks. Teachers eagerly volunteered. They understood my dilemma and just did what was needed to get the task done. They did not simply stand on the side, waiting for someone else to do the job. I have a friend who never fails to miss an opportunity. Although talented and possessing charisma, at age 45 he is still single and without a steady job. Occasionally, he asks me for a loan and I give him small pocket change; but his life, on the whole, is a mess.

I have a friend who never fails to miss an opportunity. Although talented and possessing charisma, at age 45 he is still single and without a steady job. Occasionally, he asks me for a loan and I give him small pocket change; but his life, on the whole, is a mess. As I get older, I reflect upon the life I have led. Although I cannot change the past, I sometimes feel that I could have made different decisions that might have led to different outcomes. For example, if I had decided to become the chief rabbi of a small synagogue instead of an assistant rabbi at a large synagogue, my career path might have been different. In Atlanta, circumstances allowed me to switch my professional direction, and I became a high school principal instead of a pulpit rabbi. The opportunity would probably never have come to me if I began my rabbinic career as the chief rabbi in a small town.

As I get older, I reflect upon the life I have led. Although I cannot change the past, I sometimes feel that I could have made different decisions that might have led to different outcomes. For example, if I had decided to become the chief rabbi of a small synagogue instead of an assistant rabbi at a large synagogue, my career path might have been different. In Atlanta, circumstances allowed me to switch my professional direction, and I became a high school principal instead of a pulpit rabbi. The opportunity would probably never have come to me if I began my rabbinic career as the chief rabbi in a small town. When I was a teenager, I was smitten by a beautiful girl from the Bronx. I thought we were going to get married, and I prayed to God that it all would work out. Thank God, God did not answer my prayers. If He did, I would have led a very different life from the one I lead now.

When I was a teenager, I was smitten by a beautiful girl from the Bronx. I thought we were going to get married, and I prayed to God that it all would work out. Thank God, God did not answer my prayers. If He did, I would have led a very different life from the one I lead now. In the course of my career as a high school principal, I had many faculty meetings. I would present a list of agenda items and the staff would give me their thinking on them. On occasion, a teacher would say to me that the problem under discussion was simple. All we had to do was one thing and then things would be fine. This kind of simplistic thinking in most cases did not work. The failure to see complexity doomed the suggested solution.

In the course of my career as a high school principal, I had many faculty meetings. I would present a list of agenda items and the staff would give me their thinking on them. On occasion, a teacher would say to me that the problem under discussion was simple. All we had to do was one thing and then things would be fine. This kind of simplistic thinking in most cases did not work. The failure to see complexity doomed the suggested solution. As principal of a high school, I would often interview teachers for positions in the school. Resumes often were superb, but the person had no teaching experience. I remember one candidate in particular who took pride in the fact that he had a perfect SAT score. I did not hire him because there was no empirical evidence that he would succeed, let alone survive, in a high school classroom.

As principal of a high school, I would often interview teachers for positions in the school. Resumes often were superb, but the person had no teaching experience. I remember one candidate in particular who took pride in the fact that he had a perfect SAT score. I did not hire him because there was no empirical evidence that he would succeed, let alone survive, in a high school classroom. Rescue missions are inherently unpredictable. In Israel there are many rescue narratives, the Entebbe rescue being the most famous. Before any rescue attempt is made, the plan is intensely scrutinized to obtain the optimum results: saving those in danger and making sure no one, including the rescuers, gets hurt. That is why the Entebbe rescue is so highly praised. The lives of ninety-four hostages, primarily Israelis, and the 12-member Air France crew were in jeopardy, all of whom were threatened with death. As a result of the 90-minute Israeli operation, 102 were rescued.

Rescue missions are inherently unpredictable. In Israel there are many rescue narratives, the Entebbe rescue being the most famous. Before any rescue attempt is made, the plan is intensely scrutinized to obtain the optimum results: saving those in danger and making sure no one, including the rescuers, gets hurt. That is why the Entebbe rescue is so highly praised. The lives of ninety-four hostages, primarily Israelis, and the 12-member Air France crew were in jeopardy, all of whom were threatened with death. As a result of the 90-minute Israeli operation, 102 were rescued. In Israel, I am a member of a synagogue with a large cadre of volunteers. The volunteers serve in many different capacities, each calling upon their unique talents to strengthen the infrastructure of the congregational community. One person may help with organizing the prayer service, another may focus on taking care of members who have suffered the loss of a loved one, another may be in charge of building repairs, and so on. There is a clear recognition that people are different and contribute in different ways to the overall health and wellbeing of the community.

In Israel, I am a member of a synagogue with a large cadre of volunteers. The volunteers serve in many different capacities, each calling upon their unique talents to strengthen the infrastructure of the congregational community. One person may help with organizing the prayer service, another may focus on taking care of members who have suffered the loss of a loved one, another may be in charge of building repairs, and so on. There is a clear recognition that people are different and contribute in different ways to the overall health and wellbeing of the community.